“To This End Was I Born”

Matthew 26:47–27:66; Mark 14:43–15:39; Luke 22:47–23:56; John 18–19

LDS manual: here

Purpose

To show contradictions and inconsistencies in the crucifixion story.

Reading

It’s just about curtains for Jesus. This lesson focuses on some of the back-and-forth bureaucracy of Jesus’ arrest and torture — all approved by God because you’ve got to torture someone. God’s unyielding sense of justice means that he can’t look upon sin with the least degree of allowance, and that means — by golly — someone’s got to get tortured. Unless torture is also a sin, which would muddy the waters a bit. However, I just checked, and according to the Bible, torture is just fine (especially if God is doing it). Isn’t that lucky.

Unlike in other lessons, where only one or two gospel writers comment on the same part of the story, here we get all four writers chiming in. And that means more contradictions, which we’ll cover in today’s lesson.

Contradictions should weaken a person’s confidence in the Bible. After all, if the people best-equipped to tell us what happened can’t get the story straight, then what chance do we have of finding out the details of the story? Which writer should we believe, or should we go with ‘none’? This was God’s opportunity to get his message to humankind, so how could it be that his writers muffed it? Shouldn’t this put paid to the veracity of the Bible?

According to many Christians I’ve spoken with, the answer is no — contradictions actually enhance the credibility of the Bible. The argument goes like this: even eyewitnesses see different parts of the same story, so some differences would be expected, and that’s what we’re seeing in the Bible. The real problem would be if all the versions of the gospels were written the same, because that would mean all the writers were copying over each others’ shoulders. But the accounts differ, so that makes the Bible more credible. Isn’t that something? The more contradiction, the more credibility. Which means that the Bible would be most credible if the four gospels contradicted each other completely.

Naturally, this is not how it works. When I rob banks with my friends and get rounded up by the police, we often tell them that we were out together at the time of the crime. But then when I say we were shooting pool, Lefty says we were eating at a diner, and Shorty says we were over at his place, this does not increase their confidence that we are telling the truth. (Please note: I have never robbed a bank, and this is a fictional example.) The more contradictions we find in a story, the greater the likelihood that we’re hearing a fictional story that grew in the retelling. Multiple versions of the Jesus stories wove their way through the early Christian communities, and ended up being compiled in the books we have now.

Main ideas for this lesson

Why would Judas have needed to identify Jesus?

This is odd: Judas has promised to reveal Jesus’ identity to the chief priests, Pharisees, and soldiers.

Matthew 26:48 Now he that betrayed him gave them a sign, saying, Whomsoever I shall kiss, that same is he: hold him fast.

26:49 And forthwith he came to Jesus, and said, Hail, master; and kissed him.

26:50 And Jesus said unto him, Friend, wherefore art thou come? Then came they, and laid hands on Jesus and took him.

“You know that guy you’ve been talking to and arguing with day after day? The guy that you’ve tried to kill on numerous occasions? I know you suddenly have no idea what he looks like, so I’ll point him out to you.”

Seriously, it’s very odd. One week ago, Jesus was coming through the gates of the city with everyone celebrating him by waving palm fronds. Now, no one can recognise him.

And what was the deal with kissing? You don’t have to kiss him!

Robe colour

Did the soldiers put a purple robe on Jesus?

John 19:2 And the soldiers platted a crown of thorns, and put it on his head, and they put on him a purple robe,

or was it scarlet?

Matthew 27:28 And they stripped him, and put on him a scarlet robe.

Judas’ death

In the book of Matthew, Judas hanged himself.

Matthew 27:5 And he [Judas] cast down the pieces of silver in the temple, and departed, and went and hanged himself.

But in Acts, he died from falling down and bursting, which is a revolting problem that thankfully doesn’t happen very often these days.

Acts 1:18 Now this man purchased a field with the reward of iniquity; and falling headlong, he burst asunder in the midst, and all his bowels gushed out.

Thief banter

What did the thieves say to Jesus on the cross? Matthew and Mark say they both reviled him.

Matthew 27:44 The thieves also, which were crucified with him, cast the same in his teeth.

Mark 15:32 And they that were crucified with him reviled him.

But Luke rewrote one of the thieves as a sympathetic character who got his own turn-around arc.

Luke 23:42 And he said unto Jesus, Lord, remember me when thou comest into thy kingdom.

I could go on about the contradictions involved in shuttling Jesus back and forth between Annas, Caiaphas, and Pilate, but instead I’ll just refer you here for this and many other contradictions.

No custom of releasing a prisoner

Pilate is trying to get Jesus released, so he falls back on the old ‘release one prisoner at Passover’ custom.

John 18:39 But ye have a custom, that I should release unto you one at the passover: will ye therefore that I release unto you the King of the Jews?

18:40 Then cried they all again, saying, Not this man, but Barabbas. Now Barabbas was a robber.

The problem here is that there’s no record of the Romans releasing prisoners at Passover (some discussion here). Or could it be that this is a Hebrew custom? If so, it’s not recorded anywhere in the Old Testament.

But there is absolutely no evidence that the pardoning or release of a prisoner had ever occurred, even once, before the time of Pilate. Certainly it would have been mentioned somewhere in the Old Testament if it had been a rite connected with the celebration of the Passover.

The function of this verse appears to be to shift the blame for Jesus’ death from the chief priests and onto the Jewish people generally. And that’s unfortunate, as we’re about to see.

Blaming the Jews

We’ve mentioned John’s anti-semitism, but the real prize goes to Matthew.

Matthew 27:24 When Pilate saw that he could prevail nothing, but that rather a tumult was made, he took water, and washed his hands before the multitude, saying, I am innocent of the blood of this just person: see ye to it.

27:25 Then answered all the people, and said, His blood be on us, and on our children.

This one verse has been instrumental in the persecution of the Jewish people for centuries. If they’re the ones responsible, then persecution begins to look less like bigotry and hatred, and more like God’s judgment. Convenient, isn’t it?

Kyroot comments:

Over the centuries, the blame for Jesus’s death grew from the people who were present at the sentencing and their children, to all of the Jews alive on earth at that time, to all Jews who have ever lived. It paved the way for antisemitism, discrimination, ostracism, and ultimately to the Holocaust. And all of this, or at least a very large share of it, because the author of Matthew saw fit to add this obviously fictional statement.

The writer of Heretication adds an interesting angle to this: Have you ever wondered why Jesus is always portrayed as a white dude? Probably because Jews had been vilified for so long that portraying Jesus as “one of those Jews” was unthinkable.

The justification for Jewish persecutions through the centuries has been a passage from the Matthew gospel. After Pilate has denied responsibility for sentencing Jesus to death, the Jewish people are quoted as saying “…His blood be on us, and on our children” (Matthew 27:25). A similar theme may be found at 1 Thessalonians 2:15. In Christian eyes this meant that the Jews as a race were collectively responsible for the death of Jesus. In time, the principle of collective guilt would open the way to the assignment of other imaginary forms of guilt. The fact that Jesus had been a Jew, as his parents and his followers had been, was overlooked. In Christian art the Jews were depicted as ugly and deformed, while Jesus was a handsome European.

In Western European art Jesus’ family were often depicted with blond hair and blue eyes. The suggestion that Jesus might have looked anything like a typical Mediterranean Jew was tantamount to blasphemy. He was invariably depicted wearing at least a loincloth, not only to protect emerging concepts of Christian modesty, but also to hide the uncomfortable fact that he had been circumcised, as all Jewish boys were (and still are), at the age of 8 days (Luke 2:21).

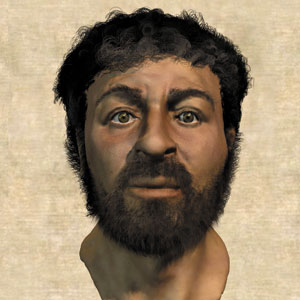

And that’s how a guy who probably looked like this:

ended up looking like this.

No, seriously, I actually know someone who’s selling the above image as a picture of Sexy Jesus.

Hmm — not so many funny memes in this lesson. Unleash the floodgates!

Here’s one that’s topical:

You know, it’s not just Jesus. Santa’s a white guy, too.

Of course, this really speaks to how our conception of God (Jesus, religious heroes, etc.) is really just a projection of how we perceive ourselves. Michele Bachmann didn’t say this, but it’s the next stop on the train.

Adoptionism

What’s behind this cry from the cross?

Matthew 27:46 And about the ninth hour Jesus cried with a loud voice, saying, Eli, Eli, lama sabachthani? that is to say, My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?

Was he feeling down? Was he quoting Psalm 22, in an effort to be literary?

My friend David Austin (personal communication) has pointed out something I hadn’t known about before.

There was a concept concerning Jesus known as “Adoptionism“. In this scenario, Jesus was “chosen” to be “adopted” as god’s son because he was a “sinless” person. God somehow “entered” Jesus at his baptism, and allowed him to perform amazing miracles etc. However when dying on the cross, god had to leave Jesus (because gods are immortal, and cannot die) and let Jesus die as a normal human. This accounts for Jesus’ final words “My god, my god, why have you forsaken me?”, as god left his mortal body.

An intriguing twist.

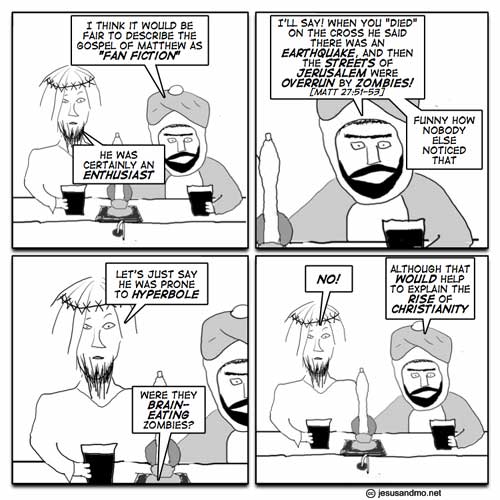

Earthquake and zombies

Ah, Matthew. The things he comes up with. When Jesus dies, he writes in a huge earthquake, and people coming out of their graves — events not reported by anyone else, either in the Bible or out of it.

Matthew 27:51 And, behold, the veil of the temple was rent in twain from the top to the bottom; and the earth did quake, and the rocks rent;

27:52 And the graves were opened; and many bodies of the saints which slept arose,

27:53 And came out of the graves after his resurrection, and went into the holy city, and appeared unto many.

Don’t you think that if this had really happened, it would be kind of a big deal? Wouldn’t someone have noticed, and reported it somewhere outside of the Bible?

Additional lesson ideas

Thy speech bewrayeth thee

There’s a little piece of English language history in Peter’s denial of Jesus.

Matthew 26:73 And after a while came unto him they that stood by, and said to Peter, Surely thou also art one of them; for thy speech bewrayeth thee.

Bewrayeth? Surely that’s betrayeth, ¿no?

No. The two words seem kind of similar in sound and meaning, but bewray is a bit different. It’s archaic, and it meant “to reveal, expose,” as with a secret.

That’s something that happens in language: when words are passing out of fashion, other similar words can step up and take over. Or a healthy word can push another word out of the way.

Well, I think that’s all the time we have for this week. Let’s have a hymn. This was one of the Thompson Twins’ best songs — see if you can spot the relevance to this lesson.

See you next week.

Recent Comments