“Fruitful in the Land of My Affliction”

Genesis 40–45

LDS manual: here

Reading

Ch. 40: We left Joseph in an Egyptian prison with a baker and cup-bearer. They both have dreams, and Joseph successfully predicts the meanings: the cup-bearer gets his job back, and the baker gets killed. Oh, thanks for that, Joseph. Some dreams are better left uninterpreted.

Ch. 41: Two years later, the Pharaoh gets a dream about seven fat cows and seven lean cows. No one can interpret the dream until the baker remembers Joseph, still languishing in prison. (Apparently Joseph has no hard feelings.) The seven fat cows are seven good years, and the seven lean cows are a crippling famine. Time to gather a fifth of all the grain. The farmers then have to buy it back, which doesn’t seem quite right. The price is their land, which Joseph moves them off of and takes for himself.

47:20 And Joseph bought all the land of Egypt for Pharaoh; for the Egyptians sold every man his field, because the famine prevailed over them: so the land became Pharaoh’s.

47:21 And as for the people, he removed them to cities from one end of the borders of Egypt even to the other end thereof.

Nice work if you can get it.

Ch. 42: Meanwhile in Canaan, Jacob and his sons are starving. Serves them right, after killing all the men of Shechem. Jacob tells them to get their butts down to Egypt to buy some grain, so they all head off, except for Benjamin. (Why not Benjamin? It’s one of those displays of parental favouritism that we’ve grown so used to in the OT. Where does Jacob get it from? Oh, yeah: god.)

The brothers must be sort of dopey, since they don’t recognise Joseph, even though he recognises them. He forces them to bring Benjamin back for a family reunion.

Chs. 43 and 44: So they do. There’s some faffing around with money in sacks.

Ch. 45: Joseph reveals himself to his brothers.

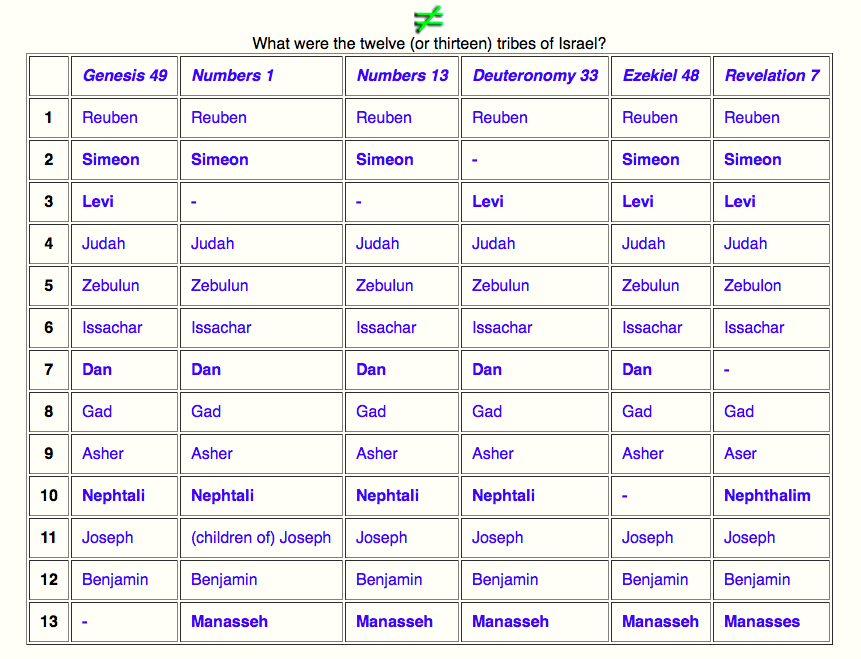

Chapters 46–50 aren’t in the reading because they’re rather tedious — enumeration of families, details of packing and moving. It does list the twelve tribes, though.

So wait a minute — which are the tribes? Well, that depends on which scripture you’re looking at.

Main points from this lesson

There’s no record of a famine in Egypt at this time.

Of course, no Egyptian pharaoh’s going to publicise a big disaster under his watch, but we can use evidence from history, archaeology, and art to tell when famines happened. One famine — a seven-year famine, to boot — happened in the time of 3rd Dynasty king Djoser, around 2670 BCE. That’s a bit early for Joseph, who made his mark around 1750 BCE, according to our trusty seminary bookmark.

While it’s possible that another one happened a bit later, and we don’t know about it, the fact that we’re able to detect one big famine from so long ago puts the literal Joseph story in some doubt.

Can you tell the future from dreams?

The story of Joseph in Egypt is a ripping adventure. With fraternal intrigue, a dash of sex, a rags-to-riches story, and Joseph’s big reveal to his brothers, it’s a real page-turner. And the story’s device — the interpretation of dreams — contributes to the story’s fantastical nature.

Leaving aside the fanciful story of Joseph, is it possible to tell the future from dreams? Many people have thought so. A quick web search will reveal loads of people telling you how, and offering anecdotes about their precognitive dreams. But if someone has a dream that later comes true, we don’t need to assume pre-cognition. A simpler and more plausible explanation involves the law of truly large numbers — there are so many people having dreams about every conceivable topic every night, and some of them are bound to come true. Here’s Robert Carroll from the Skeptic’s Dictionary:

You might say that the odds of something happening are a million to one. Such odds might strike you as being so large as to rule out chance or coincidence. However, with over 6 billion people on earth, a million to one shot will occur frequently. Say the odds are a million to one that when a person has a dream of an airplane crash, there is an airplane crash the next day. With 6 billion people having an average of 250 dream themes each per night (Hines, 50, though I don’t think I’ve ever had more than 5 or 6 dream themes a night), there should be about 30,000 to 1.5 million people a day who have dreams that seem clairvoyant. The number is actually likely to be larger, since we tend to dream about things that legitimately concern or worry us, and the data of dreams is usually vague or ambiguous, allowing a wide range of events to count as fulfilling our dreams.

Combine that with confirmation bias. If we have a dream that comes true, that’s very surprising, and we’re likely to remember it. But if we’re convinced that we can dream the future, we forget all of the things that happen that our dreams didn’t predict, and likewise we forget all of our dreams that don’t come true.

God claims responsibility for famine, and general evil.

As presented in the Bible, this famine caused servitude for some Egyptians, and death for many more. Who was responsible for this famine?

41:32 And for that the dream was doubled unto Pharaoh twice; it is because the thing is established by God, and God will shortly bring it to pass.

That can’t be right, can it? Surely god allows the problems, but doesn’t cause them. But flip forward to Isaiah a bit:

45:7 I form the light, and create darkness: I make peace, and create evil: I the LORD do all these things.

Here is a god who causes famines, caring very little if people are harmed. But he is willing to give privileged information to his buddies, if it enriches them. And in Joseph’s case, it sure does. As we’ve seen over and over again, this is not a good being, and it’s not a being worthy of worship.

Additional ideas for teaching

Joseph Smith writes himself into the Bible

Joseph Smith was an audacious fraudster, but I think his most self-aggrandising and unconvincing work was inserting prophecies about himself into Genesis 50.

From the real manual:

The Joseph Smith Translation of Genesis 50:24–38 contains prophecies that Joseph made about one of his descendants who would become a “choice seer.” The Book of Mormon prophet Lehi restated these prophecies in 2 Nephi 3:5–15. The descendant referred to in these prophecies is the Prophet Joseph Smith.

Here Joseph is on his Egyptian deathbed, and Smith gives him an extended monologue about a choice seer whose name would be “after the name of his father” — meaning Smith himself.

How transparently fictitious. ‘Literary vandalism’ is probably too strong a term for this, but this definitely qualifies as literary graffiti.

False prophecies

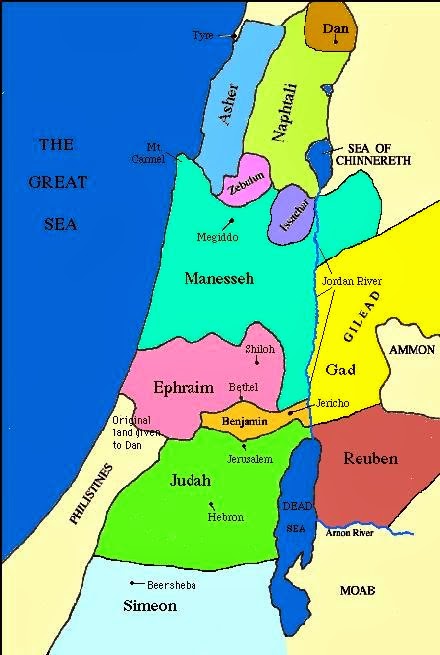

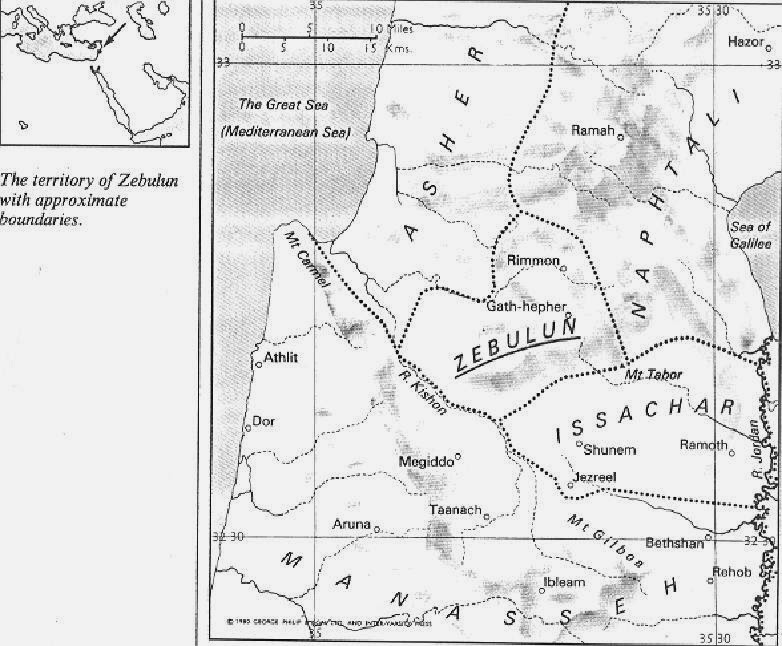

Jacob prophesied that Zebulun would be “at the borders of the sea”.

49:13 Zebulun shall dwell at the haven of the sea; and he shall be for an haven of ships; and his border shall be unto Zidon.

So when the land was parcelled out, did Zebulun ever get that beachfront property? Let’s check the maps.

Not according to this one.

Nope.

Landlocked here as well. Oh, well.

Hey, speaking of Zebulon, didja catch the reference in The Garden of Enid? I think I’ve got a crush on this girl.

Jacob’s return to Canaan

God promised to bring Jacob out of Egypt one day…

46:3 And he said, I am God, the God of thy father: fear not to go down into Egypt; for I will there make of thee a great nation:

46:4 I will go down with thee into Egypt; and I will also surely bring thee up again: and Joseph shall put his hand upon thine eyes.

…but he never did.

47:28 And Jacob lived in the land of Egypt seventeen years: so the whole age of Jacob was an hundred forty and seven years.

Did Jacob tell his son Joseph to grab his junk?

When Jacob was about to die, he made Joseph promise not to bury him in Egypt, but instead in Israel. But he did this using a curious phrase:

47:29 And the time drew nigh that Israel must die: and he called his son Joseph, and said unto him , If now I have found grace in thy sight, put, I pray thee, thy hand under my thigh, and deal kindly and truly with me; bury me not, I pray thee, in Egypt:

Put his hand “under his thigh”? Is this a euphemism for grabbing his testicles?

Sadly, probably not. Let’s get into it.

Lots of people think that gonad-fondling was a part of oath-making. Whenever this topic comes up, people seem to link it to the ancient Roman practice of grabbing a guy’s balls when making an oath. Check for example this article which notes the practice among baboons. And the word testify has more than a passing similarity to testes.

So there you have it. Open and shut, right?

Well, not exactly. If there’s one thing I’ve learned as a fan of etymology, it’s that if you find a word history that seems particularly entertaining and juicy, it’s probably completely made up.

For one thing, the word testify does not come from testicle. Testify goes all the way back to Proto-Indo-European (or PIE), which is a language so old — about 6,000 to 9,000 years ago — we don’t have any direct evidence for it. Linguists have had to reconstruct it by looking at how languages are now, and working backward. The word comes from PIE *tris- or “three”, and referred to a “third person, disinterested witness.” By the time the word appeared in Latin, it was testis. That might make you say ‘aha!’ but not so fast. The Romans applied the word to the manly articles because they were supposed to affirm a man’s virility — serve as a testament, you might say. And in fact, the diminutive form testiculus means ‘little witness’.

But did the Romans have a bit of a fiddle when testifying, at least? Not according to any evidence we have.

The putting of the hand “under the thigh” could instead mean allowing your hand to be sat on. Okay, it’s weird, but you have to admit, letting someone sit on your hand would assert their superiority over you. It would appear that the custom existed in India, so there’s a link. But that’s about as far as we can go on this one.

With all the weird stuff in the Old Testament, I was ready to believe the junk-grabbing, but when the threads all fall apart like this, it’s very suspicious, and a good sign it’s wrong. Too bad. I really wanted to believe this, but we all know how that goes.

25 March 2014 at 12:31 am

Awesome as always! Keep it up!

25 March 2014 at 10:00 pm

Daniel,

Thanks^12

When I was in boarding school a few kids used to write on their own Farah Fawcett poster (or equivalent), “Dear Tommy, thanks for last night, XOX Farah," mostly for a laugh, but half hoping some freshman would be gullible enough to believe it, which to my knowledge never did.

Seems like Joseph pulled the same stunt – but in his case it worked!

A few years ago I got an official looking "invitation" to Barack Obama's inauguration "celebration" – one of probably millions that went out to those who donated a few bucks to his campaign. There was no indication of time or place – it basically meant "show up on the mall” for the swearing in and BYOB.

Well, now I'm back in boarding school as a teacher, and a few years ago I crudely forged Barack’s signature and wrote above it, "Eric, drop by the White House in April, we'll have the basketball court installed by then and we can play some one-on-one.” I put in a cheap frame that was lying around and left it in my classroom.

You would not believe how gullible teenagers are – and I would guess that bit of fun would have worked more broadly.

It sure seems like belief is the default mode, especially when there is some level of authority delivering the information. In terms of Daniel Kahneman’s model, System 2 is lazy and just doesn’t push System I aside in unless the information carries some kind of threat or is confusing.

The psychologist Daniel Gilbert may have been on to something in his article, “How Mental Systems Believe”

http://www.wjh.harvard.edu/~dtg/Gillbert%20%28How%20Mental%20Systems%20Believe%29.PDF

He talks about a “Spinozan” (vs. a “Cartesian") model of belief formation in which “the acceptance of an idea is part of the automatic comprehension of the idea.”) That is, to understand is to believe as default and disbelief only comes with more arduous reflection – which may or may not ever come about for all the obvious reasons. This was written in 1991 and I have not yet followed up with subsequent developments along these lines. But it sure is an interesting proposal and sort of makes evolutionary sense in terms of the need in the evolutionary past to make rapid automatic decisions with Type I errors being generally less costly than Type II.